The fastest Javascript Mandelbrot in the land

re=-1.7690814562274050315843767105557415995678255069426278146980259620139710642566655442009374834559214525490298159;

im=0.00303778715253911967339488181941274068102374494645866031674381946201892057134148878778176962091542987845068523;

r=0.00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000006136366831622158191Before anything else, get going, explore the Mandelbrot Set!

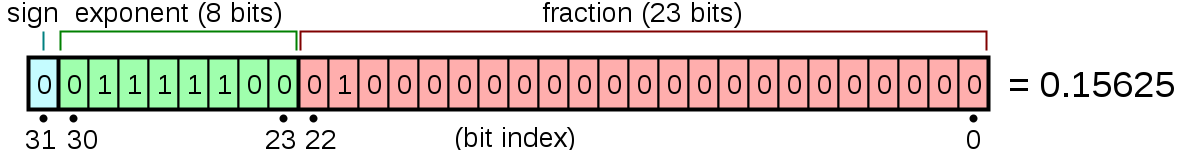

In early 2023, there was a gap in online Mandelbrot Set explorers. People had written fast, GPU based Mandelbrot Set renderers such as munrocket, but they only let you click a few times before you reached the bottom and ran into pixels. The reason is that WebGL only has 32 bit floats, and this is just not very much precision for Mandelbrot zooming. This hurts twice: First, if you naively compute in a shader, the limited bits in the mantissa (that is, the "a" in a floating point number ) run out very quickly. More cruelly, if you use perturbation theory (which I will get to shortly), the limited bits in the exponent get you. This second constraint is only noticable after you have done a great deal of work writing a complicated WebGL shader, computed a reference orbit using an arbitrary precision library, and then passed that reference to the shader as a texture, and I suspect that when people get this far and find that they can't zoom in much farther, they have historically given up.

Julia Morphing

Why is it important to be able to zoom to radiuses that are too small to represent in a 32 bit float? Julia morphing! When zooming in to the Mandelbrot Set, if you zoom near the edge of a miniature Mandelbrot Set, you will see tiny approximate Julia Sets scattered about. If you zoom in to the middle of these Julia Sets, you find more Mandelbrot Sets. However, if you zoom off center, a crazy thing happens: you eventually find a double copy of the Julia Set you picked, but doubled around the point you picked. Repeat this enough times, and you can control the image- and control enables creativity. There is a whole art scene devoted to creating images by zooming in this way, but it's currently pretty inaccessible: most tools not only need to be downloaded, but also compiled. How can we bring this experience to the browser, to any iphone that visits a website?

The problem, in detail

A 32 bit float has 23 bits of precision in the mantissa. If each click zooms in by a factor of two, this means that a naive shader can only handle 23 clicks before every pixel on the screen is represented by the same pair of numbers, which is no good. In a clever shader, instead of representing each pixel by its coordinates in the Mandelbrot Set, each pixel is represented by its difference from the center pixel. Then, as long as you have the trajectory of the center pixel stored (in my case, computed on the CPU using a WASM distribution of gmp), you can compute the trajactory of the each other pixel by

use

By computing this way, it's fine that the representation of only has a 23 bit mantissa. However, now we are limited by the exponent. The smallest nonzero number that a 32 bit float can handle is , and materially, that's only 127 clicks of zooming. The funky S at the top of this post required 303 clicks, so if we tried to render it with the clever approach listed above, every pixel's would just be 0.

An elegant solution that I reject

The right way to handle this is to give up on hardware floating point, and move to soft floats. You can store the mantissa in one 32 bit int, the exponent in another, and then make nice functions that do all the bit shifting and logic to implement ieee math. This is what early very deep mandelbrot zooms did, and real high quality mandelbrot explorers like Kalles Fraktaller and Imagina still fall back to this in some circumstances, but it's slow. They can afford this slowness because they only need soft floats once their CUDA, 64 bit shaders have run out of exponent, which takes thousands of clicks. I want to be able to zip around mildly deep in the mandelbrot set in my iphone's browser, so I need another answer.

An ugly hack (The cool kids love ugly hacks)

First, we note that in the update equation

there are a few ways that can change magnitude. The scariest way is a catastrophic cancellation between terms- this corresponds to the orbit of the current pixel diverging from the orbit of the center pixel, and is prevented using a recently discovered trick, rebasing. Second, there can be a non-catastrophic cancellation or addition that changes the magnitude of by a small factor. The third way is for to be very close to zero. If we handle all of these cases, we don't need to handle the full float specification.

We store an exponent (q) and mantissas (dx, dy). They are allowed to drift away from the range [.5, 1) unlike standard mantissas. Likewise, we store each value in our precomputed reference orbit as (os, x, y). For each iteration of

we precompute the result exponent as just q + os, the exponent of the first term, instead of keeping track of how the exponent changes for each addition and multiplication (which would be a branch for every operation). As long as the exponent is close enough to correct, (ie, right to within +- 127 or so) this works fine.

Then, we can calculate the mantissas by scaling the latter two terms to match the first.

float x = get_orbit_x(k);

float y = get_orbit_y(k);

float os = get_orbit_scale(k);

dcx = delta[0] * pow(2., float(-q + cq - int(os)));

dcy = delta[1] * pow(2., float(-q + cq - int(os)));

float unS = pow(2., float(q) -os);

float tx = 2. * x * dx - 2. * y * dy + unS * dx * dx - unS * dy * dy + dcx;

dy = 2. * x * dy + 2. * y * dx + unS * 2. * dx * dy + dcy;

dx = tx;

q = q + int(os);Now, we have handled the case of being small explicitly, and declared catastrophic cancellations to not happen. All that is left is to handle the mantissas drifting away from the range [.5, 1).

if ( dx * dx + dy * dy > 1000000.) {

dx = dx / 2.;

dy = dy / 2.;

q = q + 1;

}We keep a ...loose hold on them. Keeping the magnitude of the mantissa under 1000 instead of under 1 empirically reduces visual glitches resulting from the lack of subnormal float math on the GPU, and checking that it's not underflowing empirically can be omitted, but I don't fully know why and hope to find out in a later blog post!

The full shader code, along with the rest of the owl, is at

https://github.com/HastingsGreer/mandeljs

Finally, this work was closely inspired by Claude's article on the same topic, and for absurdly deep Mandelbrot zooms in the browser, his online explorer, while not GPU accelerated, wins out thanks to Newton Raphsom zooming and Bilinear Approximation.